Does It Matter That the President Knows Nothing About History? We Asked 3 Historians.

We are frequently reminded that the most powerful people in our country have no knowledge of or interest in history. In fact, they frequently demonstrate outright disdain. Front of center, of course, is the president, whom nobody ever accused of reading a book.

Donald Trump has suggested that Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist icon who died in 1895, is "someone who has done an amazing job" and "is being recognized more and more."

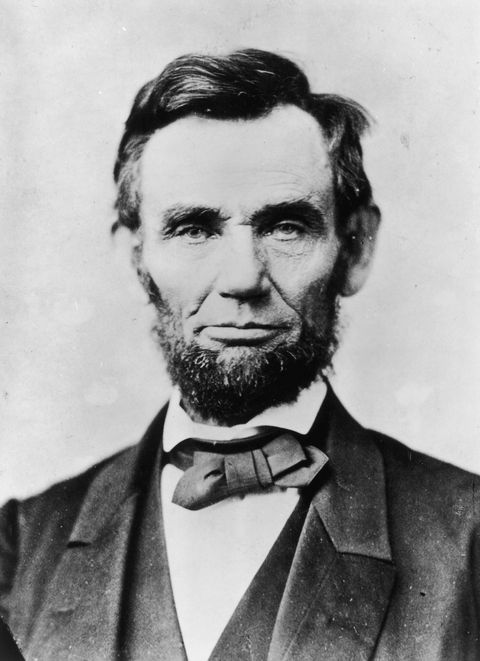

He weighed in on Abraham Lincoln: "Great president. Most people don't even know that he's a Republican, right? Does anyone know? A lot of people don't know that."

He marinated on the conflict that defined Lincoln's presidency: "The Civil War, if you think about it, why?"

He even installed a monument to a Civil War battle called "The River of Blood" on one of his golf courses, despite local historians saying, "Nothing like that ever happened there."

But we know by now that the president is no freak accident. He is the product of 40 years of conservative politics, a movement that has increasingly relied on anti-intellectualism and a disdain for expertise, which has steadily become conflated with Elitism. Conservatives can frequently be found producing "history" books, but some of the most prominent authors have issues with accuracy (Bill O'Reilly) or operate in complete bad faith to begin with (Dinesh D'Souza). It's not history if it didn't actually happen.

Trump, typically, has gone to another level. He scarcely even pretends to care, and the movement has followed suit. Just say anything—it might as well have happened. The way you can tell is that this is how one of his allies contributed to Politico's report that he did Very Presidential Things during a visit to Mt. Vernon, George Washington's historic home.

One person close to the White House said the president’s supporters aren’t bothered by the fact that he isn’t a history buff. “His supporters don't care, and if anything they enjoy the fact that the liberal snobs are upset” that he doesn’t know much history, this person said.

History is just liberal snobbery now—not a fundamental achievement of the human race that allows our civilization to advance and grow as we learn from the experience of our forebears. Or is it? Why do we study history? Are there perils when our leaders disregard it with such proud ignorance? Perhaps now is as good a time as any to ask the question—which we did of three preeminent historians. Here's what they had to say for themselves.

Tiya Miles, Professor of History at Harvard University

The study of history is the study of change; of human will, limitation and potential; of actions and consequences across the spectrum of experience. Asking why we should care about history is asking why we should care about understanding what it means to be human on this earth.

Why do we want to know about the lives our parents and grandparents lived, or about the past conflicts our communities faced, or about how those who came before us negotiated tough situations and contexts? Because knowledge of those people, events, and struggles helps us to better understand who we are, where we have been, how we might live in just relationship with one other and the natural world, and how we might navigate present challenges and the ever-present unforeseen changes around the bend of time unfolding.

Kevin M. Kruse, Professor of History at Princeton University

It's a cliché to note that history may not repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes. But like most clichés, there's a bit of truth to it. At one level, people in power need to study history because many of the problems they'll confront today have strong echoes in problems that other leaders confronted in the past. History offers lessons in what was tried before and what was not, and what worked before and what did not. But at another level, even if leaders find themselves confronting wholly new problems today, history can still help them think their way through it. The study of history imparts critical skills in assessing evidence, weighing the differences when contradictions arise, forming a coherent narrative and drawing conclusions from it.

Heather Cox Richardson, Professor of History at Boston College

History is imperative for everyone to understand, because it is the study of why and how societies change. Is it great men with great ideas who move the needle, or popular movements? Environmental challenges? Economics? Religion? Every time someone makes a decision—about a job, what preschool to put their children in, what kind of meat to buy, and how to vote—she is making a statement about how she thinks society changes, and how to create the society she wants.

But for our leaders, there is a more specific reason to understand history. From its beginning, American democracy has been a great experiment in government. In 1776, the Founders declared that "all men were created equal," and a few years later created a government in which every individual had to answer to the same laws. While they certainly hedged this idea by excluding people of color and women, it was a radical idea then, and it continues to be a radical idea today, as autocratic leaders around the world consolidate power, read their fellow citizens out of the body politic, and consider themselves above their nation's laws.

The central question of the American Revolution remains: Is it really possible for ordinary people to govern themselves?

Throughout our history, we have repeatedly faced challenges from people who thought the answer was no. During the 1850s, elite southern white slaveowners explicitly rejected democracy, explaining that the Founders were wrong and that rule by a few well-connected elites was the course of the future. They lost their bid to destroy democracy, of course, but that same impulse, born both of elite greed and popular frustration with the messiness of democracy, has repeatedly arisen since as we have negotiated the crises of expansion, world wars, nuclear weaponry, and globalization.

America remains at the center of that fundamental question: Do humans have the right to self-determination? And, if so, how can they most effectively translate that right into a popular form of government?

American leaders are players in determining the answer to that great human question. Those who do not understand history threaten to make our great experiment fail.